|

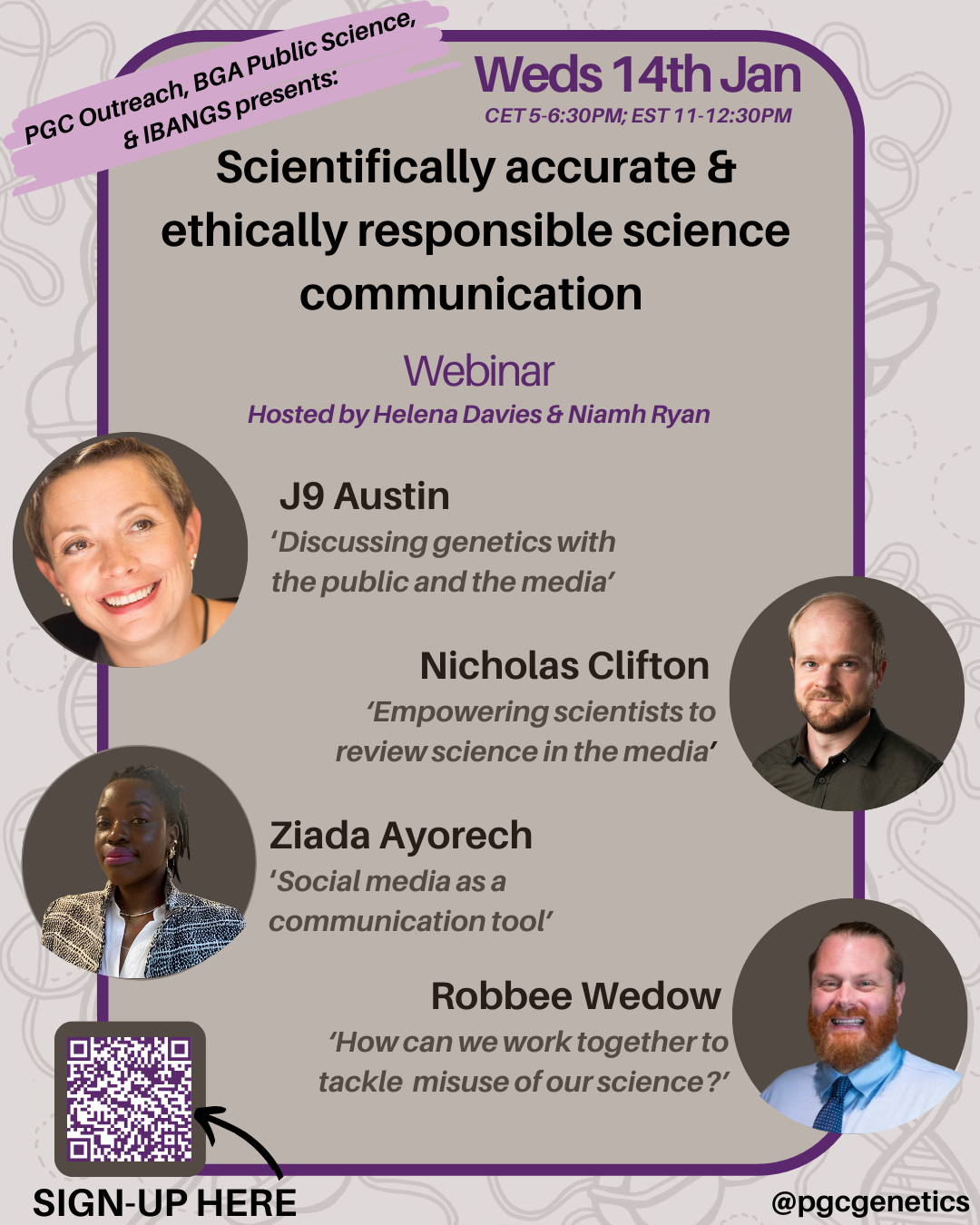

Techniques to Minimize Bias in Research IBANGS is committed to providing a diverse, inclusive, and safe society. We value diversity, equity, and inclusion across identity groups and professional levels, and are committed to professional ethics in Neuroscience and Genetics Research. More information can be found on our commitment to Diversity, Equity and Inclusion on our website [https://www.ibangs.org/diversity-inclusion-and-equity]. Experimental Design: Although researchers can’t always control how others engage with their work, researchers are responsible for designing and conducting their experiments in ways that negate or minimize bias. As examples, biomedical research disproportionately favors the study of males and often neglects sex as a biological variable, especially in animal model research (Sex bias and omission in neuroscience research is influenced by research model and journal, but not reported NIH funding - PMC); human genetic studies overwhelmingly study groups most resembling European ancestry, which may lead to increasing health disparities for underrepresented populations (Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities | Nature Genetics). These biases may exist for several reasons, such as the assumption that female hormone cycling leads to intrinsic variability or methodological limitations in the analysis of ancestry. Regardless, research shows that experimental designs embracing variability by factors like sex, gender, and ancestry, among others, improves scientific rigor, reproducibility, and discoveries (Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering | Nature). Although it is unlikely that researchers can totally eliminate bias in their work, it is important to make a concerted effort to minimize biases where possible and honestly address the biases that can’t be resolved as study limitations. Science Communication: Researchers should take steps to ensure their research, its conclusions, and its limitations are communicated clearly and with intent. A researcher’s audience does not end at the scientific community; effectively science communicating in lay language can mitigate the misconstruction of one’s findings by the general public (plus added benefit of increasing research visibility!). Lay scientific communication can be conducted through several routes: social media, video sharing platforms, syndicated news, research highlights through journals and institutes, and even lay abstracts published alongside research articles, which are gaining in popularity. Below, Goldstein & Krukowski (2024) provide some guidelines for the drafting effective lay summaries: Do:

Source: Goldstein & Krukowski 2024, Annals of Behavioral Medicine (Importance of Lay Summaries for Improving Science Communication | Annals of Behavioral Medicine | Oxford Academic (oup.com) Recently, some groups have also promoted the distribution of research FAQs for their publications that outright addresses and circumvents the ways in which research might be misunderstood or misrepresented (FoGS provides a public FAQ repository for social and behavioral genomic discoveries | Nature Genetics). Regardless of one’s preferred method to talk about their research with the public, it is important to engage in responsible communication but this is not always an easy task. Most research institutes offer research communication services that can help. Citation Bias: We also encourage all researchers to consider how citing others’ work can contribute towards mitigating bias in the field. How often a researcher is cited usually plays a decisive role in that person's career advancement, because academic institutions often use citation metrics, either explicitly or implicitly, to estimate research impact and productivity. Research has shown, however, that citation patterns and practices are affected by various biases, including the prestige of the authors being cited and their gender, race, and nationality, whether self-attested or perceived (Ray et al, 2024). We encourage IBANGS members to carefully curate the work they cite to ensure relevant papers are not accidentally excluded. Some helpful tools include a citation bias check software developed by Dani Bassett and colleagues, called cleanBIB which is freely available for download. Authors may also want to consider including a Citation Diversity Statement in their publications. |